28 New Kent Road: A Journey Through Time

- Rutuparna Deshpande

- Dec 16, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: 5 days ago

SETTING THE SCENE:

28 New Kent Road (NKR) is a pinch of land in the centre of Elephant and Castle and stands as a sign of the area's redevelopment. Currently under construction is a giant, mixed-use development of a university campus, a cinema, a shopping centre, luxury flats and a few affordable homes for locals. It is part of regeneration plans for the larger area of the Elephant, which has steadily seen its brick-and-mortar family homes replaced by high rises.

The Elephant and Castle of yesteryears probably could not imagine looking quite as neat and shiny as the new developments of 28 NKR. For instance, on the way from the Elephant to Borough Market lies the Crossbones Graveyard & Garden of Remembrance - a former medieval burial ground of paupers, prostitutes, disabled, and others who the Church considered unburiable within official grounds. Nearly half of the buried were children, and their bones were often broken, dismembered, and unmarked.

“During medieval times this particular area was the city’s primary red light district – prostitution here dates back to the Roman era – and Crossbones Graveyard became the final resting place for the thousands of prostitutes who lived, worked and died in the area. Southwark, at this time, was not controlled by the Crown, but by the Bishop of Winchester, who was responsible for the licensing and taxation of the borough’s prostitutes. As such, the women were often referred to as ‘Winchester Geese”

- Lorraine Evans, Burying the Dead, p. 95.

By 1832, the burial grounds were full to the brim and were closed down to build a school on their site. However, by 1908, the school had to close because of many bones seen sticking out of the ground. Today, the grim place is a memorial garden which was planted by local organisers (without official permission).

Similar to Crossbones, the story of 28 NKR is one of rebirths, each instance responding to the changes to life in London brought about by Britain's unfolding Imperial consciousness. While Crossbones makes the visitor aware of its unpleasant history, the commercial developments at 28 NKR have less space to hang its dirty laundry.

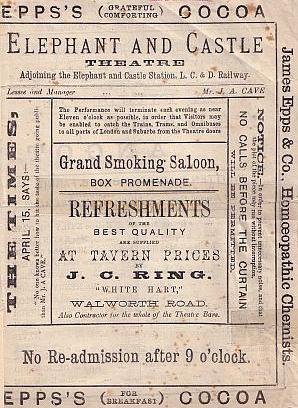

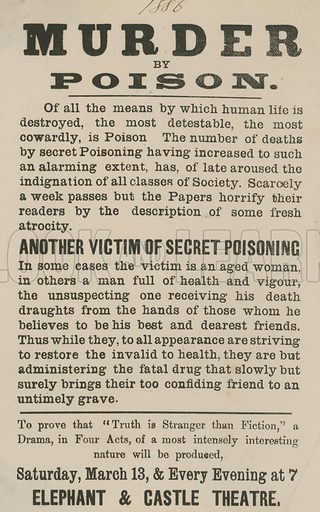

Accounts suggest that the site has been a home for a theatre since at least Shakespearean times. Before being demolished in 2021, the site hosted The Coronet Nightclub, which was preceded by a cinema hall of the same name. Before its christening as The Coronet in 1986, it was briefly run by the ABC group (which owned and operated many struggling cinema halls) from 1932. And even before that, the site hosted two rebuilds of the Elephant and Castle Theatre, one in 1872 and in 1879 after the first one was destroyed by a fire.

The Elephant and Castle theatre was noted as being part of the 'Picadilly of the South' - i.e. being the more affordable alternative to the posh West End. During Victorian times, the area surrounding the theatre was a notorious slum, where the met police dared not patrol, and bodysnatchers roamed free.

St. Stephen’s Review was a conservative periodical that ran from 1883 to 1892. The Conservatives in Parliament were staunchly against upsetting the political and social order of the British Empire, and in particular, against Irish home rule. These conservative themes - especially the anti-Irish sentiment - are forcefully present in caricaturist William Mecham’s biting caricatures.

In the above segment, the writer notes the rowdy, unruly crowd of the Elephant and Castle theatre (image 1). The ill-mannered working classes are caricatured as barbaric, uncivilised, as opposed to the erudite sons of the Empire.

Class antagonism also led to a differentiation between what was shown on the stage. Pantomimes, melodramas, romances, and blackface minstrels became popular at the Elephant and Castle theatre,

These blackface shows relied on extreme stereotyping of black men and women, particularly because there were not many black people in residence at the time. Unlike in America, where experiences of slavery and civil war anchored blackface portrayals, the working-class population of South London had only seen hypermediated depictions of what it means to be a black person from these shows.

Black people were shown to be mentally, physically and spiritually deformed and beyond saving. Existence of blackness was consolidated as a sticky identity which would go on to inspire and motivate abhorrent acts against non-white bodies across the British Empire.

The very existence of a category of 'black' served as a reminder to the white man of what he thinks he is not - animalistic, brutish, unreasoned and disfigured. In doing so, the working-class whites came to align themselves more with upper-class whites (recognising each other as one) than with the supposedly lesser subjects of the Empire.

"White men put on black masks and became another self, one which was loose of limb, innocent of any obligation to anything outside itself, indifferent to success... and thus a creature devoid of tension and deep anxiety. The verisimilitude of this persona to actual Negroes... was at best incidental.

For the white man who put on the black mask modelled himself after a subjective black man - a black man of lust and passion and natural freedom (licence) which white men carried within themselves and harboured with both fascination and dread."

- Sophie Neild, Popular Theatre 18995-1940 in The Cambridge History of the British Theatre Vol.3: Since 1895

With the height of the British Empire in the early 20th century came an increased influx of trade, people, and ideas into their recognisable foreign form right within the Imperial core.

Demand for a more 'authentic' novelty experience of seeing 'real' black people prompted many theatres to begin supporting touring acts from the US, often featuring former slaves. The arrival of black workers competing with white ones aroused the familiar tussle between the immigrants and 'natives'.

“IMPORTED NEGRO

ARTISTS UNWELCOME”

- The Era Magazine, LONDON, 1923. Headline: “No Cabaret and No Negroes”

The Era was Britain’s main show-business weekly for a century, and it was widely read within the theatrical world. Page 10 of its issue of 7 March 1923 carried a piece based on a letter sent by the Variety Artists’ Federation to the authority responsible for entertainments in London – the Clerk of the London County Council.

[to be continued ...]

Comments